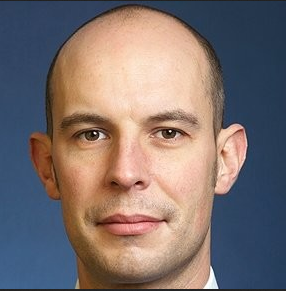

Andrea Orcel Appointed Santander Group CEO

| By Fórmate a Fondo | 0 Comentarios

Further to the announcement of 25 June 2018 which confirmed Rodrigo Echenique’s decision to retire from his role as Executive Vice Chairman of the Group and Chairman of Banco Santander Spain at the end of 2018, the Board of Directors of Banco Santander announced that José Antonio Álvarez will succeed Echenique as Vice Chairman of the Group and Chairman of Santander Spain. Following this appointment Álvarez and Bruce Carnegie-Brown will be the Group’s two Vice Chairmen, with Álvarez being the only one with an executive role.

Furthermore, following an intensive selection process carried out with the support of external advisers, the Board of Directors has decided that José Antonio Álvarez will be succeeded as CEO of the Group by Andrea Orcel, subject to regulatory approval. Orcel is currently member of UBS Group’s executive committee and brings a wealth of experience and expertise, having worked closely with Santander for almost two decades.

These appointments are expected to take effect in early 2019 following regulatory approvals.

Ana Botín, Executive Chairman of Banco Santander, said: “Rodrigo Echenique has been my most trusted advisor and played a fundamental role within the Board and as an Executive Chairman of Santander Spain. I now look forward to José Antonio Álvarez assuming these key strategic and executive responsibilities. The Board and I want to express our thanks and deep appreciation for Rodrigo´s commitment and great added value to Santander over the past 30 years and look forward to his continued support from his non-executive board role. We wish him and his family the best in his retirement from his executive roles. I very much look forward to continuing to work with José Antonio as a trusted partner, as we have done over the past four years. He has been critical to the successful execution and delivery of our plans and is a great role model for everything we want the Santander culture to be. As Executive Chairman of Santander Spain, he will complete the Banco Popular integration, as well as support and represent the bank and me personally on strategic decisions through his executive committee and board roles. Andrea Orcel’s international experience and strategic expertise further strengthen our existing team, helping ensure we continue delivering on our current strategy as we have for the past four years. He brings a deep understanding of retail and commercial banking, as well as a strong track record in managing diverse teams across Europe and the Americas in a collaborative way. This will help us achieve our ambition to build the best retail and commercial bank, as well as a global digital platform, whilst preserving our proven subsidiary model.

During the last four years, Santander has put in place a new management team both at the Group level and in the main markets, and launched a strategy based on growing loyal customers and embedding a common culture with its 200,000 employees. This has allowed the bank to become one of the best-rated in the industry for customer service in the majority of its core markets.

Santander launched its strategic plan in October 2015, and expects to deliver on all the objectives it set. By the end of 2018, the bank expects to have almost doubled the number of digital customers it serves, from 16 million in 2016 to 30 million, while the number of loyal customers has increased by 40% to 19.1 million. During the same period, Santander has strengthened its capital base significantly – adding over €16 billion euros to its CET1 to 10.8% at Q2 2018, while also increasing the cash dividend per share by 132%.

In early 2019, Banco Santander will publish its new medium-term strategic plan. The updated plan will be based on the same pillars which have guided the bank over the past three years: a relentless focus on customer loyalty, and a goal to become the best retail and commercial bank in the markets in which we operate, whilst building an integrated digital platform across the Group.

Botin continued, “We have a unique and strong base of 140 million customers across both developed and high-growth markets. We are building upon this solid foundation by creating an open financial services platform that brings the best products, services and technology to our customers. We are now strengthening the top team, with a goal of accelerating the execution of these plans, sharing the best practises and innovations across the Group for the benefit of all of our businesses and countries.”

José Antonio Álvarez said: “I am very excited to take over the Chairmanship of the best bank in Spain. We face many important challenges including the integration of Santander and Popular networks, and especially to make Santander in Spain, the best in the entire Group.”

Andrea Orcel said: “I am exceptionally proud and excited to be joining Santander as CEO and working with Ana, José Antonio and all of the organisation as we continue to ensure Santander excels. My immediate priority is to meet as many of my new colleagues as possible, and gain a new perspective on Santander from them. The financial services’ sector cultural and business transformation continues at an accelerated pace with increasing headwinds and disruption. Rather than fight those challenges, winning organizations embrace them, are energized by them and turn them to their advantage to catapult themselves forward building long lasting competitive advantage. I have no doubt that with us all working together to make the most of Santander’s strong culture, brand and global franchise, we will continue to be one of those winning organizations.”

These changes continue the trend of the last few years of building a more diverse and international team and Board. With new CEOs in our key markets of Mexico, Brazil, the UK, US and Spain, the Group´s management today better reflects the diversity of its footprint. In the Corporate Centre, similarly, the leadership team includes almost fifty percent internationally-experienced executives, including talent from Germany, Italy, the UK and the US.

The Board of Directors of Banco Santander will be composed of 15 members, of which the majority, eight, are independent. Santander’s board has gender diversity (more than a third are women), multiple nationalities (American, Brazilian, British, Italian, Mexican and Spanish) and broad sector representation (financial, distribution, technology, infrastructure or the university).

Andrea Orcel has been appointed by the Board of Directors by co-option to replace Juan Miguel Villar Mir’s seat on the Board of Directors. Villar Mir has presented his desire to leave the Board as his tenure expires. The Board wishes to express its appreciation for his contribution and dedication during his years as a director.