From 1998 until now, two macro trends have influenced international wealth planning and international taxation:

1. Tax homogenization or cartelization (which implies a global rise in taxes and the undoing of any traces of tax competition); and

2. The encroachment on individuals’ privacy (necessary to reach the objective above).

Both trends gained momentum after the 2001 WTC attack right up until Donald Trump’s leadership push and they seem to be acquiring even more relevance as we speak.

To illustrate this, it is important to remember that, between the attack and Trump’s rise to power, the following changes happened (among others), all of them leading towards the trends mentioned above:

1. The “Patriot Act” was passed;

2. Low or null taxing jurisdictions were forced to abolish bearer shares, and in many cases to require companies established there to register directors’ names before authorities (unlike several states of the U.S.);

3. FATCA was passed and enacted; and

4. The Common Reporting Standard was passed and enacted.

Just like Trump’s Presidency stopped the advance of invasion to privacy (for example, IGA signing for FACTA implementation with third-country parties was halted). It implied, in fact, not just a halt but also a step back regarding wide agreements between high tax

jurisdictions leading to a revival of tax competition once championed by Ronald Reagan. Biden’s victory, and above all, the pandemic have caused a fast return to the trends discussed above.

In between Trump losing the 2020 elections and his stepping down from office, Congress ignored his veto over the National Defense Act and forced its passing. This Act included the “Corporate Transparency Act,” which, in a nutshell, established the obligation to communicate to FinCEN the final beneficiaries of any company incorporated in the U.S.

It is uncertain how FinCEN will process such a huge amount of information – but what is not uncertain is that this provision will lead to an incredible erosion of an individuals’ privacy, with or without justification.

As for the second topic, taxes, Yellen’s words are still very fresh. “The U.S. should not have an issue with increasing its corporate taxes as it will not lose investments because this action forces the world’s countries to cooperate”. It is impossible to provide a better definition of tax cartelization.

In Latin America, both trends are the order of the day.

Starting with taxes; three countries have already approved taxes on extraordinary wealth (or on great fortunes), using the pandemic as an excuse. These countries are Argentina (made worse by the fact that Argentina, together with Uruguay and Colombia, already had a wealth tax before the arrival of Covid-19), Bolivia, and Chile.

Although a part of the world has long left this kind of tax behind, essentially because it is counterproductive for countries growth, difficult to manage, and a violation of the principle of equality, as well as for being one of the most evaded taxes, in some Latin American countries it seems to be gaining momentum due to the losses caused by the ongoing pandemic and the appearance of new populist governments.

Until recently, out of the 35 countries in the region, there was an equity tax, a personal property tax, or a wealth tax only in three of them. These countries were Argentina (besides the highest rates and the lowest minimum taxable amounts), Colombia, and Uruguay.

Towards the end of last year, Bolivia became the fourth country in the region to have this tax type. On December 28 of that year, the Bolivian parliament passed a tax on fortunes about 30 million Bolivianos reaching 152 people in Bolivia and a second wealth tax (in theory, for the only time) in Argentina. According to the information shared by the President of Bolivia over social media, the government authorities on economic matters estimated that with the new provision, around 100 million Bolivianos would be collected (approximately USD 14.3 million).

Argentina and Bolivia are remarkably different from each other, in particular:

- Firstly, as I mentioned before, there already was a tax on personal property in Argentina, which makes this additional tax unconstitutional, as it affects the same assets twice. And since the deadline for payment of this tax was originally March 30, there are already several court filings requesting precautionary measures against it or a declaration of unconstitutionality);

- Secondly, Bolivia’s tax reaches wealth ranges above USD 4,300,000, while in Argentina, it must be paid above USD 2,420,000;

- In Argentina, rates for this tax vary from 2% to 3% for assets in the country and from 3% to 5.25% for assets owned abroad; in Bolivia, rates are 1.4% for persons with wealth ranges between USD 4.3 million and USD 5.7 million; 1.9% for wealth ranges between USD 5.7 million to USD 72 million; and 2.4% for wealth ranges above that; and

- The new tax in Bolivia will be paid on an annual basis and permanent for all persons living in the country, including foreigners, having property, deposits, and securities in the country and abroad; this is not the case (so far, at least) in Argentina because there is already a personal property tax there, annual and with rates which may climb to 2.25%, with a practically null threshold.

Besides the provisions passed in Argentina and Bolivia, there is a bill heavily underway in Chile and more or less incipient rumours or projects, sometimes with less backing, in Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, and other countries.

In Chile’s bill, the two main differences with the cases above are the following:

- The Chilean threshold is USD 22 million (similar to the US minimum for the inheritance tax, in line with the banking world’s standards for great fortunes); and that

- There being a high level of juridical security in the country, likely, this “extraordinary,” “one-time-only” tax will actually be so. In Argentina, there have been numerous examples of taxes passed for a certain amount of time, then extended for decades (such as the earnings tax, the personal property tax, the check tax, the increase in the VAT rates, and so on).

Our position on this tax, whatever the specifics in each country, remains the same as always: there really are only four types of taxes: taxes on earnings, consumption, transactions, and equity, and the latter is by far the most dangerous and debilitating for any country. I would propose that a tax on current wealth is nothing but a tax on future poverty.

Going back to the issue of individuals’ privacy, another unfortunate trend in Latin America is the passing of a variety of provisions making taxpayers notify tax authorities of their wealth planning, which violates not only the privacy of persons but also principles as basic as they are important, such as attorney-client and accountant-client privilege.

In this case, Mexico took the first step through a law passed by Congress on October 30, 2019, which entered into force on January 1, 2020. One of the effects of this law was to include the Tax Code of the Federation, the obligation, not just for taxpayers but also their tax advisors, to reveal fiduciary structures leading to a fiscal benefit.

Not unusually, after Mexico, Argentina followed suit, with AFIP’s General Resolution 4838, currently under study by several Nation’s Judges.

The revival and strengthening of both trends, not just in Latin America but the entire world, compels us to investigate current wealth structures in order to get ahead of greater changes and speed up the creation of innovative fiduciary structures for clients who have not yet done so. The growing fiscal voracity of countries will likely lead to completely legal structures now, but this could not be the case in the not-so-distant future.

All in all, there are storm clouds ahead in the wealth structuring and wealth preservation space.

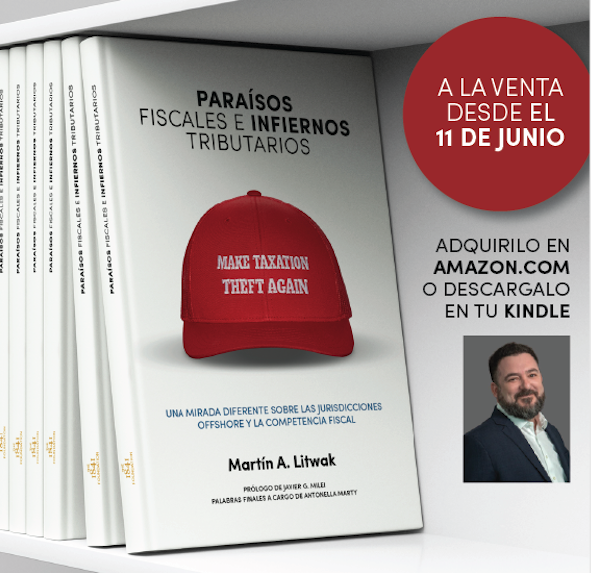

A column by Martin Litwak, founder and CEO of @UntitledLegal, a boutique law firm specialized in fund investment, corporate finance, international wealth management, exchange of information and fiscal amnesties as well as the first Legal Family Office in the Americas. Litwak is the author of the books “Cómo protegen sus activos los más ricos (y por qué deberíamos imitarlos)” (How wealthiest people protect their assets and why we should do the same) and “Paraísos fiscales e infiernos tributarios” (Tax havens and tax hells).