As the new year dawns, investors are turning the page on a tumultuous chapter, opening a new – hopefully more boring – one. We leave behind four tumultuous years marked by the pandemic and its policy countermeasures. The macroeconomic volatility was so acute that historical charts for most indicators now resemble seismographs.

Output, consumption, employment, and income all plummeted in 2020, only to rebound forcefully in 2021. Inflation and interest rates followed suit, fueled by the war in Ukraine’s impact on energy markets. With inflation out of control, the Fed, initially anchored to zero rates, had to shift gears, and embarked on the most aggressive tightening cycle of the last three decades.

Most variables, including inflation, have been gradually normalizing, and in the latest FOMC meeting, the Fed finally hinted at potential rate cuts this year. This outlook could mark the start of a new business cycle. In the initial expansion phase interest rates decline and corporate profits grow, generally positive for bonds and equities; at this stage investors typically focus on corporate earnings rather than the cycle’s sustainability, helping to keep volatility subdued.

However, financial markets are forward-looking. By the time the cycle fully blooms, much of the recovery could already be priced in. This was evident with major indices hitting all-time highs by the end of 2023, despite stagnant corporate earnings and the 10-Year US Treasury yield reaching levels not seen since 2007. Historically, valuations and interest rates tend to revert to the mean, suggesting bonds might outperform equities in 2024.

The big question remains where interest rates will settle once inflation fully normalizes. The answer may differ between the short and long ends of the yield curve. Given the economy’s resilience to higher rates, the Fed may lean towards avoiding excessive rate cuts, retaining some “dry powder” in reserve to support the economy when needed. According to FOMC projections, the overnight rate is expected to stabilize around 3%.

Long-term interest rates are a different story. After their decade-long descent, even into negative territory in some countries, they surged dramatically last year to pre-Great Financial Crisis levels, causing significant losses for bondholders. The drivers behind this shift remain unclear, and the market continues to calibrate wildly. Should the era of unconventional monetary policy finally end, bonds could regain prominence in portfolios.

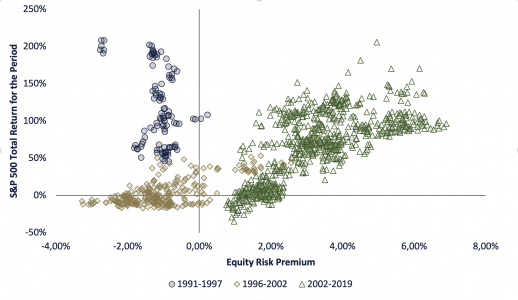

Similarly, equity markets appear to be undergoing their own regime shift. Risk premiums, which remained comfortably above their long-term average during the ultra-low-rate era, have compressed significantly over the past year. However, the case for equities rests ultimately on earnings growth, not valuations. Price-to-earnings, price-to-book, and risk premium over bonds are all static measures telling us whether equities are cheap or expensive based solely on the current earnings picture.

A more useful approach is to think of valuations as a “bar” that future corporate profits must clear to justify current stock prices. When valuations are low, it is easier for earnings to hop over the hurdle. This is the appeal of buying equities on the cheap, you have more margin for error. However, blindly focusing on low valuations would have led investors to miss out periods of stellar equity returns, not to mention investing in companies like Amazon or Tesla, whose valuations defied traditional metrics.

The chart below showcases how low risk premiums could lead to both great and dismal S&P 500 returns five years later. Conversely, high risk premiums have historically been a strong harbinger of positive returns. With the risk premia close to zero, we may be entering a new kind of normalcy, out of the ultra-low-rate comfort zone but far from the dotcom-era exuberance. This comparison is particularly pertinent because the potential technological leap with AI could echo the transformative impact of the internet.

Regardless of the Fed’s pivot, interest rates are going to remain elevated for some time, impacting borrowing costs for governments, corporates, and individuals. This process of economic normalization also means that we cannot endlessly bank on consumer resilience or fiscal support to prop up the economy. These may prove to be headwinds for earnings growth and the sustainability of the cycle.

As we bid farewell to the pandemic era, investors should not forget that there is an ever-present risk of “Black Swan” events. Geopolitical tensions simmering across the globe and the looming uncertainty of the US presidential elections are just two prominent examples. “Return to Normalcy” was the slogan used by President Warren G. Harding to win the 1920 election as the country emerged from another pandemic, the Spanish flu. Despite the similarities, the reuse of this slogan by any of the current presidential candidates could prove, at the very least, highly controversial.