My position on the creation of Registers in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) is well known and, in this commentary, I will fully explain my reasons to reject this potentially very harmful (and unnecessary) initiative.

In my opinion, there are at four relevant arguments worth exploring as they put my stance on the right side of history. There are none, as far as I can see, for the opposing view.

Privacy

When the Income Tax was first created, with the main aim of covering extraordinary expenses (like wars), the current arguments used by detractors against taxes were not why private individuals had to pay for crises they had not created, or even why the Government thought that it was appropriate to “rob” citizens in order to do so, but what many among us still see and defend as something fundamental in these times: the individual’s right to privacy.

Mid-19th century taxpayers thought the Government had no right whatsoever to know how much money they earned. They were already paying consumption taxes and they were not willing to let the Government meddle with their private lives.

Income Taxes evolved over time: one war led to another, and even in the absence of armed conflict, inefficient governments decided to impose them without any extraordinary circumstances. And so, more and more countries started to adopt them.

As a result, individuals started to seek ways to avoid these taxes lawfully, often by using structures in jurisdictions where this type of tax was considered akin to expropriation. They also created juridical structures aiming to protect their privacy. There is nothing to condemn in either behavior and BVI, alongside other jurisdictions that have created a framework for these business opportunities, has played a crucial role in this industry, providing the best context for these individuals to achieve their wealth planning goals.

Let us add that offshore jurisdictions were not created to capture investments by other countries’ fiscal residents, but it was the latter that drove away their own citizens by overlaying exorbitant taxes (on their income first and then on their assets) leading to an unsustainable amount of fiscal pressure. Then, continued intrusion into individual freedoms reached levels considered too high by those individuals who think privacy is an unalienable right.

The solution to this tension is not that complicated at law: When two different, individual rights oppose each other, the arising conflict is always resolved by determining which right prevails in hierarchy. When there is a “conflict” between a fundamental human right and a mere interest of the State, there can be no discussion.

Personal safety

This section would not be relevant if the entire world enjoyed the levels of legal certainty and personal security of the U.S. or Europe. This is not the case. And the vast majority of BVI users live in insecure countries, most of them in Latin America, Asia and Africa, where unfortunately violence is already part of their day to day lives.

For these individuals, the critical need for privacy that was discussed above is also relevant for other reasons. In fact, these individuals are people who live in countries where the need to protect wealth does not have anything to do with the desire to pay less taxes or the right to privacy as a right in itself (which would, of course, be understandable), but to protect their physical security. In Latin America, for example, crime levels are extremely high and that includes kidnap for extortion of high-income citizens, theft, torture and murder. What is the use of privacy then? To protect assets, of course, but also to protect life itself.

Forty-two of the 50 most violent cities in the world in 2020 are in Latin America, most of them in Mexico and Brazil. Out of the remaining 8, Durban and Mandela Bay in South Africa, and Kingston, Jamaica, stand out. Only two are in developed countries: St. Louis and Baltimore. As for the countries with the most extortion kidnappings, Brazil tops the list with 54.91% of incidents, followed by Mexico with 23.40%.

The BVI SOLUTION already exists

In BVI, there is an established system that allows authorities to know the identity of the shareholders and owners of the companies established in the territory in a matter of hours if necessary: the notorious BOSS, copied and implemented by many competing jurisdictions.

We do not deny, that under certain circumstances, this information must be provided to the authorities. Unlike those who criticize our position with regards to implementing this new BO Register, we put ourselves in their shoes and we tell them that they are right in their aims, but not in their arguments or, even less, their proposals.

In other words, the interests that this new Register is intended to protect are appropriately protected already. There is no need for further infrastructure: why would we reinvent a wheel that is not broken?

Economic arguments

If the world ever adopts this idea holistically, the offshore industry will be effectively cancelled. This would be a death knell for BVI, other offshore jurisdictions and the individuals using them with strictly lawful goals.

But why get ahead of ourselves and give away our lifeblood on a silver platter to other jurisdictions when the existence of public registries of UBOs is far from being a world standard nowadays? This would be one of the most detrimental political decisions the jurisdiction could make as it will lead to loss of business and the migration of trust and wealth planning companies out of BVI.

My fear would be that companies doing business in the BVI would be forced to move their operations and clients to jurisdictions which will not have these registers in place, such as Belize or Nevis, in order to maintain some sense of privacy for their clients. We would also face scrutiny from HNW and UHNW advisors and clients in emerging markets with regards to them having to place themselves and their clients in harm’s way in order to comply with this Register. This is simply not good for business.

Means and ends

Again, it is clear that governments have a legitimate interest in knowing the wealth status of their taxpayers, but as I always say: sometimes, the cure can be worse than the disease. What is the cost? Is this worth it if there are other, less invasive, mechanisms that lead to the same result? Do we need to lose all aspects of privacy to conform to what a few people think is the solution?

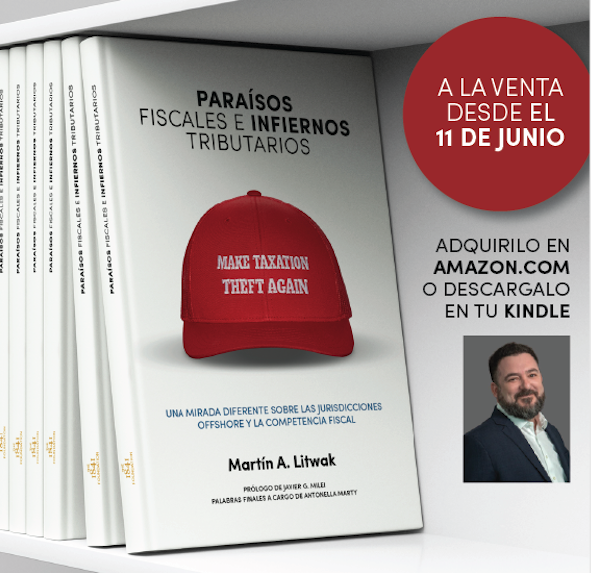

Column by Martin Litwak, lawyer specialised in international wealth management and investment fund structuring