The past 30 years have seen a bigger improvement in human prosperity than all of the past centuries combined. We have built more roads, buildings and machines than ever before. More people are living longer and healthier lives and access to education has never been better.

The average GDP per capita has grown 15-fold since 1820. More than 95 per cent of newborns now make it to their 15th birthday, compared with just one in three in the 19th century.[1]

However, such progress has come at a great cost. As humanity has thrived, nature has suffered.

Humans are driving animal and plant species to extinction and destroying their habitats to feed and house an ever-increasing population. An influential UN report warns that up to one million animal and plant species are at imminent risk of extinction.[2]

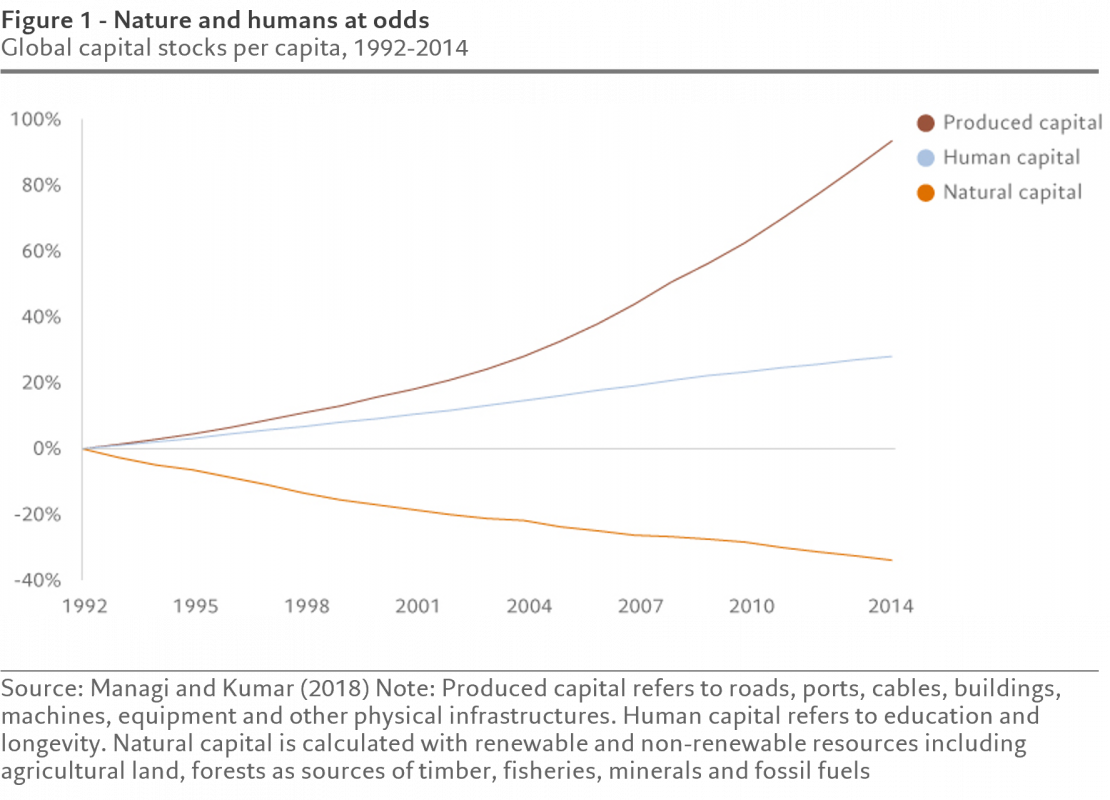

Data shows that, in the 1992-2014 period, the amount of capital goods – such as roads, machines, buildings, factories and ports – generated per person doubled. Over the same timeframe, however, the world’s stock of natural capital – water, soil and minerals – per person declined by nearly 40 per cent.[3]

Policymakers now consider biodiversity protection as urgent a priority as halting global warming.

The UN COP15 biodiversity summit in Montreal in December is expected to unveil ground-breaking targets to protect nature. Ahead of the landmark event, world leaders meeting in Egypt for the COP27 climate conference in November recognised nature’s role as a key solution to fighting global warming.

According to the draft agreement, the Montreal Accord will commit signatories to restore at least 20 per cent of degraded ecosystems, protect at least 30 per cent of the world’s sea and land areas and reduce pesticides by at least two-thirds.

Once these targets become national policy, policymakers and regulators could quickly establish a framework for biodiversity protection and disclosure, with the Paris Accord and net zero as the template.

Biodiversity finance: a burgeoning market

Intensifying political and regulatory efforts are a step in the right direction. But policymakers cannot turn the tide on their own. Businesses and investors must also do more to place the world on a path to sustainable growth.

As stewards of capital, investors are uniquely positioned to help build an economy that works with, rather than against, nature.

They can play a crucial role by helping to shift capital flows away from businesses and projects that degrade the natural environment and towards nature-positive solutions.

Historically, biodiversity finance has tended to focus on raising money for conservation activities within a philanthropic framework. More recently, however, a market for biodiversity and natural capital investment has been steadily growing, including securities that explicitly aim to minimise biodiversity loss and capitalise on the potential for long-term capital growth.

There have been high-profile launches of funds investing in companies specialised in biodiversity restoration and ecosystem services in the past couple of years, with nine out of eleven such funds having debuted since 2020. Assets under management in this group have more than doubled to USD1.3 billion from just USD525 million at the start of the decade.[4]

Funds investing in biodiversity and natural capital aim to help embed more sustainable and regenerative business practices across a whole value chain, involving industries such as agriculture, forestry, IT, fishery, materials, real estate, consumer discretionary and staples, utilities and pharmaceuticals.

The Food and Land Use Coalition estimates that efforts to transform current food and land use in favour of regenerative and circular practices have the potential to create a biodiversity market worth USD4.5 trillion by 2030.[5]

Nature-positive transition

The finance industry must add its heft to the global effort to reduce the damage, while also enhancing nature’s recovery. One influential research initiative geared to helping this endeavour is the Finance to Revive Biodiversity (FinBio) research programme, which is overseen by the Stockholm Resilience Centre at the Stockholm University.

The four-year research programme, of which Pictet Asset Management is a founding partner, aims to develop valuable research that should help the finance industry transform current practices, which reward growth at the expense of biodiversity, to a new model which accurately captures – and attaches an economic value to – the nature-positive quality of a business.

The initiative brings together a diverse consortium of academic and financial-sector partners, including the UN Principles for Responsible Investment, the Finance for Biodiversity Foundation and Oxford University.[6]

Nature has always been the economy’s most important asset. It is time the finance industry recognised that.

For the latest research on biodiversity and why it is a financial risk you cannot ignore, click here.

Notes

[1] Our World in Data

[2] IPBES

[3] Source: Managi and Kumar (2018) Note: Produced capital refers to roads, ports, cables, buildings, machines, equipment and other physical infrastructures. Human capital refers to education and longevity. Natural capital is calculated with renewable and non-renewable resources including agricultural land, forests as sources of timber, fisheries, minerals and fossil fuels

[4] Broadridge and Pictet Asset Management, data as of 31.07.2022

[5] https://www.foodandlandusecoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/FOLU-GrowingBetter-GlobalReport.pdf