From March 2022 through the publication of this article, the Fed raised its funds rate target 525 basis points to 5.5%, a nearly 23-year high. The funds rate target is now set more or less in line with the 1982-2008 average of 5.31%, up significantly from the period of near-zero rates that ran through most of the 2008-2021 period. The implications of interest rate (or cost of capital) normalization will reverberate through balance sheets, correlations, portfolio construction and portfolio management.

Regarding balance sheets, a gnawing question bandied about the financial press and market participants is whether there is too much debt in the system. This topic is always a concern from a macro perspective. Still, from an investment manager’s and portfolio’s perspective, the question should be, “Are you selecting ‘good’ balance sheets and avoiding ‘bad’ balance sheets?” A disciplined selection process between balance sheets is one of the hallmarks of successful fixed income investing.

In today’s fixed income environment, concern is emerging around the impact of inflation and rising labour costs on corporate balance sheets. Still, even more unease is developing around government balance sheets. We believe the current budget situation is a risk and one of several headwinds we are currently experiencing in the market. There will be more and more Treasury issuance, and the Treasury plans to term out some of this new paper, which means potentially more supply further out the curve. That, combined with the Fed’s quantitative tightening as it slowly winds down its balance sheet, inflation pressures deriving from labour, oil or lingering supply chain hiccups, are all part of the mosaic pushing the cost of capital higher and feeding expectations that the new era of normal interest rates will be here for the longer term. It’s the new normal.

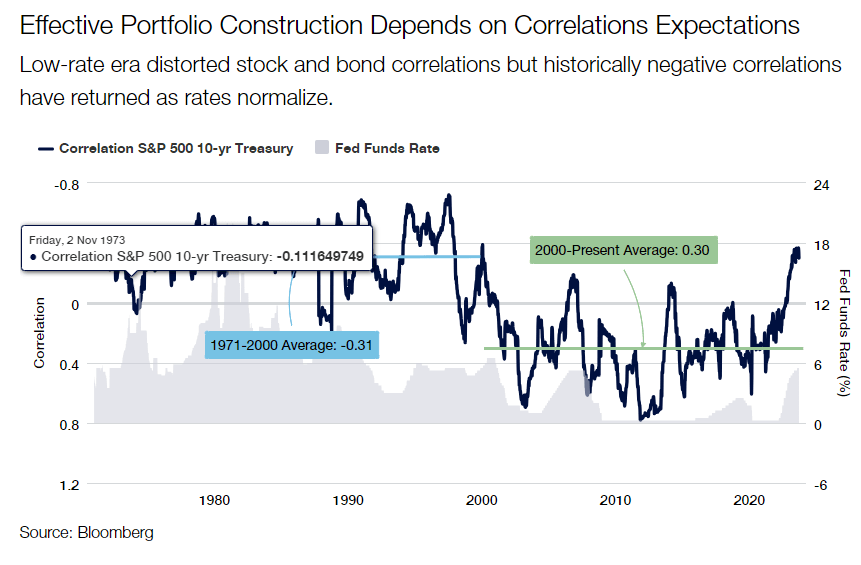

Regarding correlations, a critical change resulting from the higher interest rates is that it forces investors to wrestle with how bonds will fit into a broader portfolio going forward. As with balance sheet selection, the normalization of interest rates impacts fixed income’s role in portfolio construction. Recall that during the low-rate era, which goes back to about the year 2000 (during the dot-com bust when the Fed pushed its funds rate down as low as roughly 1% in 2003), the correlation between fixed income and equities turned positive and stayed there for about 20 years – nearly a generation.

Bonds performed well because interest rates were declining, and the resulting drop in the cost of capital drove equities higher. This period is fondly (or not so fondly in retrospect) remembered as the Greenspan, then Bernanke, then Yellen “put” as successive Federal Reserve leaders extended the Fed’s role beyond its traditional mandates to include suppressing excessive equity market volatility and keeping equity investors happy. It was not until 2022 that the Fed finally rid itself of this perceived obligation. That occurred when correlations spiked back into negative territory in tandem with the current tightening cycle.

In other words, with the normalization of interest rates, it’s reasonable to expect a return to negative correlations between fixed income and equity performance, as we saw before the low-rate era that dawned in 2003. During the 30 years from 1971 through 2000, the correlation between stocks and bonds was -0.31. That correlation flipped to +0.30 from 2000 through today, even considering that correlations normalized back to about -0.30 in recent months.

Regarding portfolio construction, the shift in cross-asset correlations has two significant consequences: First, bonds can behave differently from stocks in how they perform directionally. Secondly, fixed income is re-establishing its traditional role as ballast in an investment portfolio because there is actual yield in holding bonds. Over time, fixed income holdings help dampen portfolio volatility. The market takes care of itself, rather than the Fed taking care of the market.

From a portfolio construction perspective, asset allocators may now use fixed income to dampen the volatility of their equity holdings, provided the normal negative correlations between the asset classes continue. Given the likelihood of the Fed’s “higher rates for longer” mentality in the current inflationary market environment, negative correlations should extend into the foreseeable future.

We expect market volatility to rise as central banks no longer desire to suppress the cost of capital to push demand forward and stimulate growth. With increasing volatility comes the risk of dislocation, which, in our view, calls for managing fixed income portfolios and fixed income asset allocation with a much more agile and flexible approach. That contrasts with many managers’ predominant ‘siloed’ approach to improved income management.

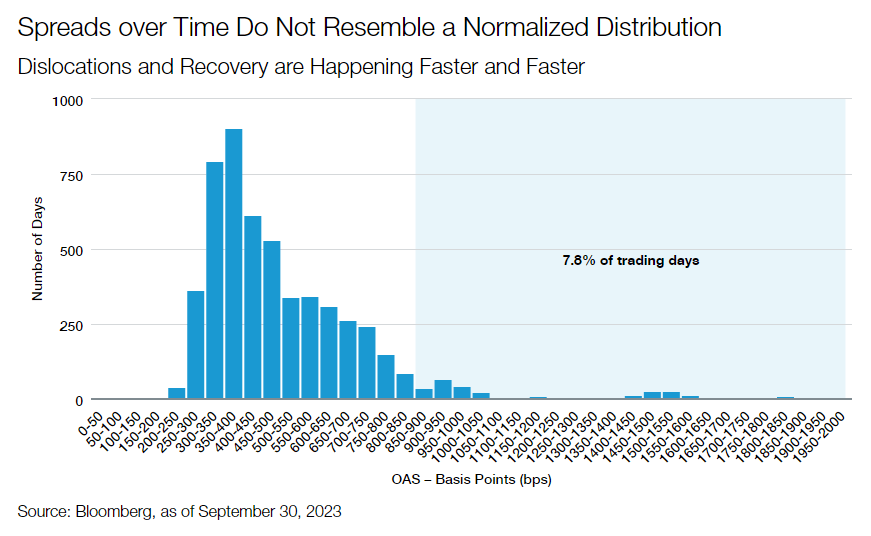

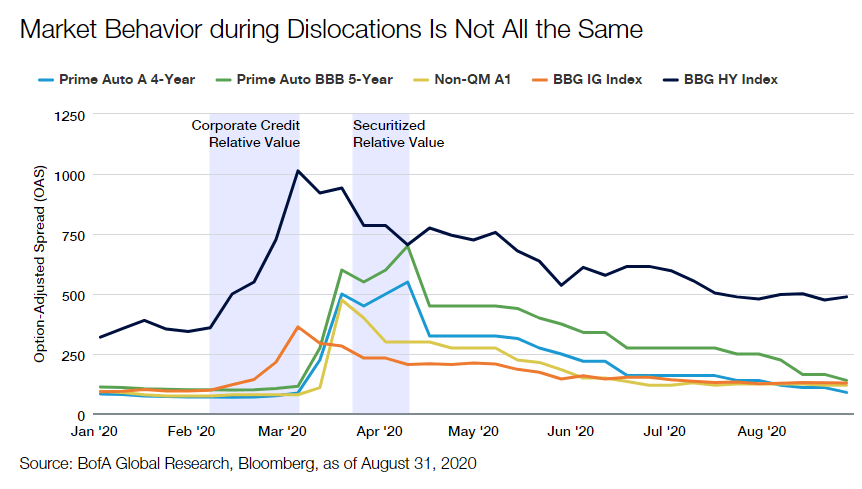

The speed at which credit spreads widened and recovered has increased remarkably over the past decade, most notably during the COVID crisis. During the dot-com bubble, high yield spreads blew out to more than 600 bps, and it took about three years for spreads to narrow to below that mark. During the Global Financial Crisis, it took high yield spreads about a year to complete the widening to narrowing cycle. Fast forward to the COVID crisis, and that same cycle took just one month. Why has this cycle shortened so much? Look to the Fed. The Fed has learned to utilize a variety of liquidity measures, tools, and communication to steady financial markets during each subsequent crisis. It doesn’t mean another era of zero interest rates is around the corner. Still, it’s essential to understand how much more effective central banks have become at providing support during uncertain situations.

This affirms our conviction that flexibility concerning a manager’s investment style and an investor’s asset allocation decisions will hold greater importance in achieving successful outcomes. These outcomes are where active management’s skill and agility should provide a distinct advantage over passively managed fixed income portfolios. From a portfolio management perspective, we favour having a defensively minded approach for most of a market cycle to allow the rotation into attractively priced assets when markets sell off.

This style of management will likely be increasingly important going forward. Dislocations are increasingly more nuanced. Suppose you want to outperform and generate robust returns and income for your investors. In that case, managers need to understand that different markets dislocate at different times, even within a broader market sell-off. Within that period, if you are executing and making decisions faster, you can earn attractive excess returns across different sub-markets as value appears.

Another source of income in the fixed income markets is the ‘pull to par’ effect. Income matters, and savvy managers can boost returns during a period of high coupon securities. Agile investors may add lift returns by selecting bonds issued during the low-rate period but are now trading at a discount. As these bonds return to par closer to maturity, that provides impetus to aggregate returns.

For investors, we believe the implications of the new era of income focus on 1) the role of fixed income in the broader portfolio and 2) how best to capture value in an environment characterized by higher rates and higher volatility.

Investors need to re-evaluate how the fixed income asset class will behave from a return, risk, and correlation perspective. Higher rates and positive real yields allow fixed income to reassert itself as a provider of ballast to the broader portfolio. With the central bank ‘put’ in hibernation, it is possible to see the correlation return to, and remain, negative as was the case for markets before 2000.

We believe higher rates will be coupled with higher volatility. A moderate market dislocation occurs once every 2-3 years, and we expect this trend to continue. For investors, this means incorporating more flexibility in how managers capture opportunity and how allocators manage asset allocation. We think ‘style box’ investing will be more challenging – higher volatility favors strategies with a broader opportunity set and managers who quickly capture dislocation. Allocators, if possible, should incorporate this flexibility into their own decision making, as downside protection and the ability to reallocate capital to dislocated markets can enhance long-term excess returns.

Opinion article by Jeff Klingelhofer, co-head of investments and Managing Director for Thornburg IM.

Important Information

Investments carry risks, including possible loss of principal.

The views expressed are subject to change and do not necessarily reflect the views of Thornburg Investment Management, Inc. This information should not be relied upon as a recommendation or investment advice and is not intended to predict the performance of any investment or market.

Please see our glossary for a definition of terms.

This is not a solicitation or offer for any product or service. Nor is it a complete analysis of every material fact concerning any market, industry, or investment. Data has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but Thornburg makes no representations as to the completeness or accuracy of such information and has no obligation to provide updates or changes. Thornburg does not accept any responsibility and cannot be held liable for any person’s use of or reliance on the information and opinions contained herein.

This is directed to INVESTMENT PROFESSIONALS AND INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS ONLY and is not intended for use by any person or entity in any jurisdiction or country where such distribution or use would be contrary to the laws or regulations applicable to their place of citizenship, domicile or residence.

Thornburg is regulated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission under U.S. laws which may differ materially from laws in other jurisdictions. Any entity or person forwarding this to other parties takes full responsibility for ensuring compliance with applicable securities laws in connection with its distribution.