Until recently, by maintaining a watertight capital account, China deliberately postponed its membership of the reserve currency club. A few years ago, China had grown to be a giant in the world of trade, yet remained a dwarf in the world of capital. More recently, the People’s Republic reached a point where – given its rapidly increasing economic size and trade footprint – this contradiction was no longer sustainable or sensible.

The next phase in China’s economic renaissance is now well underway. It is actively pursuing its twenty-first century manifest destiny to regain the mantle it lost in the 1830s: being the world’s largest economy. This means it must expand its role in global capital markets to match those it has already achieved in global trade. This will balance the two windows through which China looks at the world – and just as importantly through which the world looks at China. Being a member of the reserve currency club is but a stepping stone on the renminbi’s path to achieving that worldwide acceptance, and especially in China’s efforts to master the world of capital. Expect a new Shanghai-Hong Kong-Shenzhen triptych to become one of the world’s three main fountainheads of capital and the next pit-stop on China’s road to global economic pre-eminence.

For this to happen sustainably however, China will need to move from being an exporter of capital – born of running a current account surplus – to being an importer of capital – which follows on from running a current account deficit. This answers the Triffin Dilemma which says that to have a truly acceptable reserve currency, one needs to produce a surplus of that currency so that third parties can hold it. Only when the appetite of China’s consumers for foreign goods exceeds that of foreigners for China’s goods – when China runs a current account deficit – can this be truly achieved.

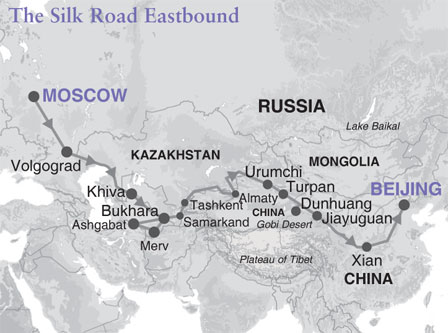

In the interim, China has to find a way of recycling its trade surpluses so that foreigners get easy access to its currency. Here Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy doctrine – the One Belt One Road programme – achieves this aim. By forcing Chinese surplus capital abroad to revive the terrestrial Silk Road of Central Asia and its maritime equivalent through the Indian Ocean, China is repeating what Britain did in the late nineteenth century: establishing its reserve currency status first by investing its trade surplus abroad before, one suspects, the eventual rise of the import-hungry Chinese consumer spreads the renminbi worldwide ‘naturally’, after China’s current account stops being a surplus and instead becomes a deficit.

Michael Power is Strategist at Investec Asset Management.