Last week, Google announced that it would acquire Wiz for $32 billion, marking its largest acquisition ever. Wiz, which offers cloud security solutions, was founded in 2020 and by the end of 2022 was already valued at $6 billion. By 2023 the company had achieved $100 million in recurrent revenue “ARR”, and by YE-2024 the company was reported to reach a stunning $500 million in ARR, demonstrating a unique capacity to grow sales at an impressive pace. Wiz received venture backing from its onset. Its first institutional round was for $20 million. Those early investors, which included the famous Sequoia Capital may reap close to a 100X gross over their original investment.

Venture is the one category within the private assets world that it is not actively raising capital from the wealth industry, yet certainly exploring options on how to. It’s also the riskiest and probably least understood space of private investing, although nowadays there’s a never-ending sleuth of podcasts and articles to learn about it.

Accessing and selecting VC funds is also complicated. The one easy path for retail investors is to participate in venture-backed companies when these become public through an IPO. Once publicly traded, VC funds will typically maintain their position until they find the right moment to exit, potentially generating better outcomes for investors, keeping their board seats and therefore their influence. Not all VC-backed companies go public though, many exits occur through strategic acquisitions as in the case of Wiz.

VC-backed companies raise money through capital rounds, starting with seed and all the way to growth capital. At the seed stage, a particular technology or service may still be a project in paper and the funds would be used by the founders to kickstart the company. Once the growth stage is reached, the company typically has proven sales and customers. Capital would be employed for expansion projects through marketing, hiring top performing sales professionals or developers, amongst other initiatives. From seed to growth to a potential IPO, an average VC-backed company would have raised capital about 6 to 8 times throughout a cycle of 10 years or more, although the amount of capital and number of rounds required varies.

The VC industry has historically been recognized for being able to generate exponential results over relatively small investments. A good example is Amazon: it took only two rounds of outside investor funding (the second by a venture fund) for a total of $9 million to help it achieve self-sustainability and its future valuation.

However, cases like Amazon and Wiz are true outliers, even within the VC universe: they resulted in outsized returns for institutional backers. Double or even triple digit multiples are quite rare yet are targeted by all VC funds as they represent a fundamental element of the industry: the power-law.

You will hear that VC is a power-law industry meaning in practical terms that for any number of investments, it is only a very limited number of those that explain the returns of a venture fund. Imagine for instance a seed fund that made a series of investments and 10% of capital returned 100X. No matter what happens to the rest of the portfolio, that fund would have achieved at least a 10X gross (10% times 100).

As mentioned above, very high returns (in the order of 50X or above) are extremely rare (less than 1% of all seed investments made) whereas capital loss due to projects failing can exceed 50% in any given seed fund. Devoid of power-law results, seed funds would likely provide poor returns for investors.

Alas, not all VC investing relies solely on a model where a very small fraction of invested capital drives all returns. Growth-venture is a more accessible space as funds that focus on this category tend to be much larger than early stage ones and typically invest in companies that have a proven track record, reducing the probability of capital loss. Entry points and prices though can be substantially higher than at the seed stage and therefore return expectations for specific investments tend to be lower. Wiz for instance was valued at about $70M when it got its institutional seed checks back in 2020 but it raised a growth round at the end of 2021 at the aforesaid $6B valuation. Compared to its destined exit value of $32B, that is more than a 5X growth multiple in value achieved in only 3-4 years, which is still impressive.

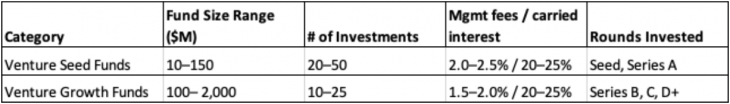

The message: growth venture can still produce very attractive returns, relying on a model in which investment periods are expected to be somewhat shorter and capital losses lower relative to seed investing. The table below compares some characteristics between these two categories.

Typical characteristics of seed and growth funds (using data for Vintages 2012 to 2022)

Source: produced with Grok Artificial Intelligence application. Carta Q2 2024 (fund sizes), PitchBook Q3 2024 (fund sizes up to $2B investments, rounds for 2012– 2022), Cambridge Associates (2024) (stage definitions for 2012– 2022).

Can I invest in venture?

This article covers a limited scope of the VC industry and some of its characteristics. Note that VC fund styles can vary and be more flexible in terms of investing strategy. Multistage funds, for instance, can invest in seed, core venture (which we did not touch upon in this article) and growth. Some of the most recognized VC funds actually fall under the multi-stage category.

VC funds are generally limited to qualified purchasers through traditional drawdown funds. Achieving top quartile returns in venture requires investing with the most recognized managers of the industry. To begin with, access to startup funding varies across VC funds: it is not a plain level field. It is widely recognized that founders tend to favor the most reputable funds and their partners, who often are invited first to invest in top-tier projects. However, accessing these partnerships is a time-consuming exercise. Typically, it is the purview of institutional investors and teams who focus on manager selection and nurturing relations with GP’s. In some cases, being invited to a capacity-constrained venture fund can take years of insistence.

Given this condition, an adequate allocation strategy for qualified retail investors is to commit to a fund of funds “FoFs” with demonstrated access to some of the top names. Interestingly, FoF’s nowadays may even accept capital commitments as low as $100K, providing proper diversification. Some of these may even incorporate co-investments in their approach to have direct exposure to companies like Wiz.