I recently came across an old newspaper article from February 1989 that described Beijing’s residential property “bubble,” with average selling prices then of about US$430 to US$510 per square meter. The article went on to say that, given that the average college-educated worker typically saved less than approximately US$13 per month, at those prices, it would take a century or so to be able to buy a two-bedroom apartment. The writer concluded that a housing bubble was underway.

These days, the official average Beijing home price has reached a new high of approximately US$3,800 per square meter (or about US$246,000 for a small one-bedroom apartment) despite strict home purchase restrictions. In terms of affordability, consider that last year, China’s average annual take home pay per person for urban households was approximately US$3,900. China’s property bubble has been a hot topic probably ever since the beginning of the country’s commodity housing development. But despite some compelling arguments and striking examples that a bubble does exist, China’s property market has generally remained robust. So, is its property market really in a bubble? If so, why has the bubble lasted so long?

Real estate in the country’s urban areas is expensive by traditional metrics. But the average income has also more than tripled over the past decade. While true wages may not continue to grow at double-digit rates, by the same token, it may be too soon to jump to the conclusion that there is a real estate bubble while incomes continue to shift upward.

No doubt that China has some poorly planned large-scale projects developed. Like the U.S., China is a vast country filled with many contradicting examples. Observers could reach opposing conclusions about the U.S. property market by narrowing in on areas such as San Francisco or Detroit. To generalize about China’s market can be equally misleading.

In previous commentaries on China’s housing market, we have noted that the typical down payment requirement for first time home buyers is a hefty 30%, and usually 60% for a second home. Unlike in the U.S., mortgage loans in China are recourse loans. As a result, a homeowner cannot expect that any remaining debt can be forgiven should he or she not be able to continue payments. So the systemic risks are very different than those the U.S. faced in recent years.

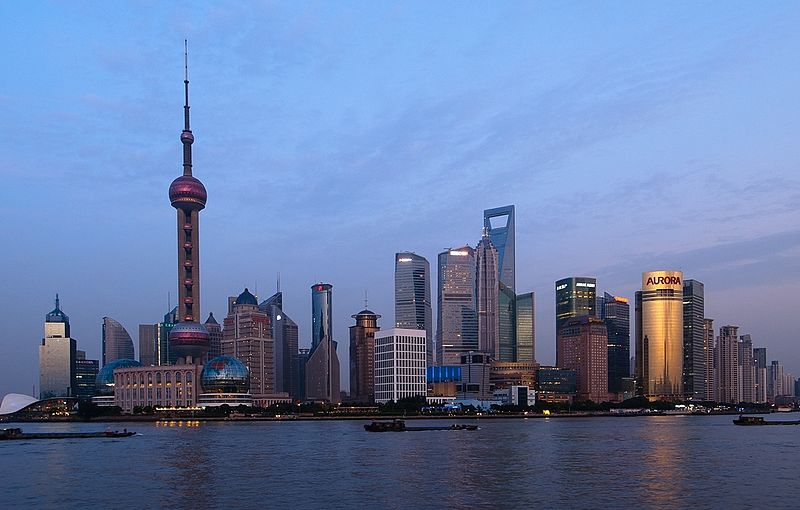

So what factors have underpinned the property bull market over the years? The main driving force for the development of property market has been actual demand for urbanization and home upgrades. Some investors are really concerned over the rate at which people in China may be buying multiple properties for investment. Chinese are famous for having high savings rate—as high as about 50%. However, the country’s investment alternatives are currently limited, and low bank rates have meant that keeping money in the bank has been a sure way to lose purchasing power. China’s domestic equity markets are also notoriously volatile. In addition, given the steady appreciation of China’s currency, the renminbi (RMB), over the past decade, the incentive for investing in RMB assets has become more appealing. Buying real estate, therefore, has been one of the few alternatives available for people to preserve wealth and purchasing power, especially in light of the typically low costs incurred for housing investments, or carrying costs. In China, so far only two cities, Shanghai and Chongqing, have implemented experimental property tax programs. The low carrying costs also help explain why some flats sit vacant—the need to find rental income is much less pressing than it might be in the U.S. where you have to cover higher mortgage costs and property taxes.

Although China’s property market certainly exhibits some bubble symptoms on the surface, the root cause seems deeply embedded in China’s economic growth and financial system. The government has proposed different measures over the years to tackle property inflation, but the efforts have been largely unsuccessful as they only temporarily suppress the symptoms. With continued wage growth and urbanization, China’s property market may be a tough “bubble” to pop.

Henry Zhang, Portfolio Manager at Matthews Asia

The views and information discussed represent opinion and an assessment of market conditions at a specific point in time that are subject to change. It should not be relied upon as a recommendation to buy and sell particular securities or markets in general. The subject matter contained herein has been derived from several sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of compilation. Matthews International Capital Management, LLC does not accept any liability for losses either direct or consequential caused by the use of this information. Investing in international and emerging markets may involve additional risks, such as social and political instability, market illiquidity, exchange-rate fluctuations, a high level of volatility and limited regulation. In addition, single-country funds may be subject to a higher degree of market risk than diversified funds because of concentration in a specific geographic location. Investing in small- and mid-size companies is more risky than investing in large companies, as they may be more volatile and less liquid than large companies. This document has not been reviewed or approved by any regulatory body.