The renminbi has been on a fairly consistent depreciating path versus the China Foreign Exchange Trade System (CFETS) renminbi index (the basket of trading partners’ currencies that Beijing implemented in December 2015), with some volatility around big moves in the US dollar spot index (DXY), points out Investec.

Initially the renminbi strengthened against the US dollar as the American currency generally weakened over the first half of 2016, but it weakened against the CFETS basket – a goldilocks scenario that helped China to contain capital outflows, as investors capitulated on their long view on the US dollar.

China has also benefitted from the UK’s unexpected vote to leave the European Union, said expert´s firm. The market shock that accompanied the result on 24 June, enabled Beijing to weaken in the RMB against the CFETS basket without causing market panic, as it had done on previous devaluations. The People’s Bank of China decided to manage the renminbi “with reference to a basket”, but it has not kept it stable, instead allowing the currency to depreciate steadily.

“We have seen the pace of depreciation at times up to 20% annualised”, says Mark Evans an analyst in the Emerging Markets Fixed Income team, “but it would be hard to expect that pace of depreciation going forwards without it triggering more capital outflow pressures. We believe that depreciation of around 8% or so feels about right on the longer term.” While there is likely to be some volatility, we expect the exchange rate to be stable near-term ahead of one important policy event: October’s renminbi inclusion in the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket of currencies, which effectively confers global reserve currency status.

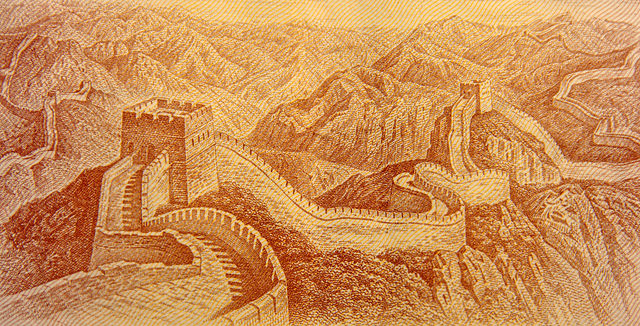

China Global integration

An important aspect of integrating China into the global economy, remarks Investec, is the internationalisation of the renminbi. This aim advanced in December last year when the IMF agreed to include the Chinese currency in its SDR basket. There were, however, questions about whether the renminbi met all the criteria. By including the currency in the SDR basket the IMF hoped to encourage China to fully liberalise the renminbi by 2020. But in fact, it appears that the reverse has happened. The renminbi’s share of payments via the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) network has fallen over the past year from a high of 2.79% in August 2015 to just 1.96% at the end of June 2016.

Surprised by the volatility and weakness over the past year, investors and corporates have reduced renminbi deposits held in banks in Hong Kong, Taiwan and South Korea over the past year. While investment inflows, which indicate willingness to hold Chinese assets, have also fallen 38% over the same period.

Beijing’s unpredictable policymaking history of the past year or so – state intervention in the stock markets and sudden currency devaluations – has also played its part. “We expect more policy clarity once we know the identity of the top echelons truly calling the shots after the leadership transition of the Politburo Standing Committee next year,” says Wilfred Wee, portfolio manager in the Emerging Markets Fixed Income team.