Many market watchers interpreted the September U.S. jobs report as a bit of a disappointment, as jobs growth came in slightly weaker than expected. But I think it was a decent report, fairly in line with where I expect the U.S. economy to be given that it’s moving on two tracks.

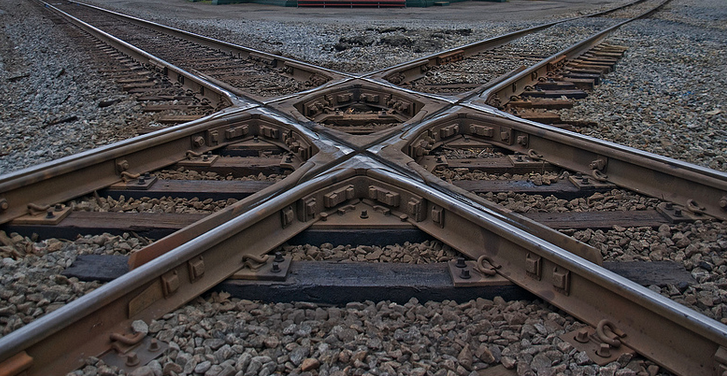

What do I mean by that? We’re currently witnessing a U.S. economy in which both consumption and employment in the services sectors have been amazingly robust, while expenditures and employment in good-producing segments remain softer. The September report showed this longstanding trend is continuing, with strong employment growth in service sectors, such as health care and education, and especially in professional business services (up a strong 67,000 last month). In contrast, the manufacturing sector lost another 13,000 jobs, continuing short-term and long-term trends. In fact, manufacturing employment peaked in June 1979, roughly four decades ago, with nearly 20 million jobs in the sector (or 1 in every 5 employees). At its trough in 2010, there were only 11.4 million manufacturing jobs in the U.S. (or less than 1 in 10 employees).

There are both demographic and technological underpinnings behind this two-track trend, as an aging population and innovations in technology boost employment in service industries that tend to be much more labor intensive.

September’s labor force participation rate numbers are another sign of the trend, showing strong demand for human capital in today’s new economy is sending more people back into the workforce. Indeed, the participation rate has rebounded from 2015 lows, and is now back around 63%. See the chart below. The recent uptick in labor force participation is even more impressive when judged alongside an aging population, as many more people are exiting the workforce today (i.e., retiring) than we’ve experienced in prior decades.

The U.S. economy is also running along two separate tracks in another sense. We’ve seen strong employment growth in recent years, but merely decent levels of reported gross domestic product growth. Some say the incredible employment numbers reflect a poor-productivity economy. These arguments suggest that we have needed to hire many more people to produce a relatively smaller amount of goods, as if production and labor output were diminished in their ability to generate aggregate output. I believe this is a misguided interpretation of the economic landscape due to the fact that traditional productivity and output numbers don’t capture the downward influence of new technologies on prices.

The bottom line: The two-track trends evident in the September jobs report are just more signs that the U.S. economy is doing better than headline numbers may imply. So where does this leave us from a monetary policy perspective? The Federal Reserve can, and will likely, move policy rates at its December meeting, barring an unexpected shock to the economy or markets.

Build on Insight, by BlackRock written by Rick Rieder.