You have to go back to the early 1970s to find the last time that oil production increased in the US. However, at that time demand was also increasing at a much faster rate than production and thus the positive impact of rising oil output was more than offset by growing imports. By contrast, and as a result of changing demographics and improving efficiency, demand is currently declining and this trend is likely to continue.

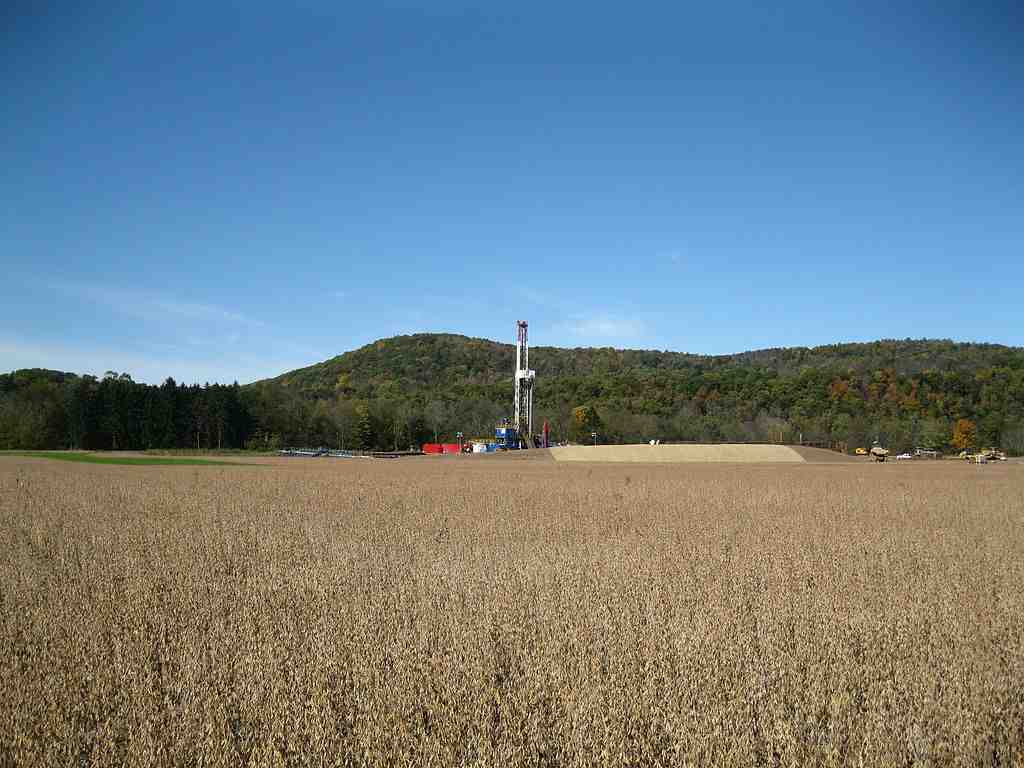

The technological advances that enable oil and gas to be extracted from shale, and Washington’s support for the exploration and production industry are the key factors behind the significant growth in energy output, a trend that will continue for several years. As a consequence, the US is now materially less dependent on oil imports from outside of North America – it imported 40% of its oil requirements in 2012, down from 60% in 2005. This decline in dependence on foreign oil has major implications for the global economy and geopolitics.

The production of natural gas from shale formations has rejuvenated the natural gas industry in the US. The US is singlehandedly relieving the pressure on OPEC and helping oil prices to recede from levels that have rationed demand for over two years. Consequently, one of the essential preconditions to improved global growth, namely adequate and preferably abundant supplies of reasonably-priced, oil-based energy, is now in place.

North America will add a further 0.8 – 1.0 million barrels per day (mbd) of production by the end of 2013 (to put this in context, the US consumes around 18 mbd), and at current crude oil prices this trend will continue. Meanwhile, tougher fuel standards, driving the development of more efficient trucks and cars, will likely keep oil imports on a downward trend.

The inclusion of ethanol highlights the fact that as a result of the implementation of the Renewable Fuels Standard in 2005, the US effectively linked grains and oilseeds to crude oil. As the world’s largest exporter of agricultural products, it has been able to command much higher prices for farm products, boosting another industry and the entire Midwest economy. This augments the economic advantage accruing from the shale energy revolution and reinforces North America as the engine of improving global economic growth.

The changing relationship between the dollar and commodity prices will be the most disruptive feature, because this relationship has prevailed for 40 years. Essentially, fewer dollars will be spent outside of North America to support the US’s 18mbpd (and declining) level of oil consumption. Combined with the flow of investment money into the US, which is supporting increasing energy production, as well as related industries such as chemicals and engineering, and the general recovering economy, the dollar will likely enjoy a period of sustained strength. Given that this development will take place amid strengthening global growth, which will tighten commodity markets, we anticipate that this will result in a period of strong commodity prices together with a robust dollar.

In addition to the macroeconomic impact described above, it is reasonable to extrapolate that US foreign policy, especially as it applies to the Middle East, may be influenced by the rapidly declining dependence of America on OPEC production. A study by Germany’s foreign intelligence agency, the BND, for example, concluded that Washington’s discretionary power in foreign and security policy will increase substantially as a result of the country’s new energy wealth, and that the potential threat from oil producers such as Iran will decline. Moreover, the development of energy resources in the US is taking place at a time when several Middle East countries are undergoing seismic political changes. This background only reinforces the US as the preferred target for investment and increases the likelihood that oil prices will remain elevated into the foreseeable future.

Opinion column by David Donora, Head of Commodities at Threadneedle