The disparity in views seen in the updated September dot plot regarding the official rates’ positioning at the end of 2024 has become more turbulent this week.

While the median projection suggests up to three additional rate cuts (with nine bankers projecting 4.375%), there are seven others who only see two cuts. On the extremes, one banker anticipates cuts of up to 1%, which balances the two more conservative members who believe only a 0.25% reduction may be necessary from now until December.

This lack of clarity within the U.S. central bank has become more evident this week. Mary Daly of the San Francisco Fed, who supported the unexpected decision to review the Fed Funds by 0.5%, sees no immediate reason to suspend plans for monetary policy easing.

Nevertheless, calls for a more cautious approach are growing. Among them, Lorie Logan (Dallas) and Jeff Schmid (Kansas) have shared their thoughts this week. Schmid explained: “Although I support reducing the restrictive stance of monetary policy, I would prefer to avoid exaggerated moves, especially given the uncertainty about the final direction of monetary policy and my desire not to contribute to financial market volatility.”

Similarly, Neel Kashkari (Minneapolis) favors a slow approach toward the neutral rate (R*, estimated around 3% according to the projections). Productivity improvements in the U.S., a significant increase in the workforce (largely due to immigration since 2021), and structural recovery in consumption following the deleveraging after the subprime crisis could justify an R* higher than suggested by the Fed’s model (Laubach-Williams-Holston). If this is the case, a 0.5% cut, along with six other cuts expected by economists through 2025, could risk overheating the economy.

Even the private sector calls for restraint. In an interview with Bloomberg, Brian Moynihan, CEO of Bank of America—after pointing out that the Fed has been behind the curve since 2022—called for prudence in adjusting the cost of money. He noted that the risk of “moving too fast or too slow (in adjusting official rates) is now greater than six months ago.”

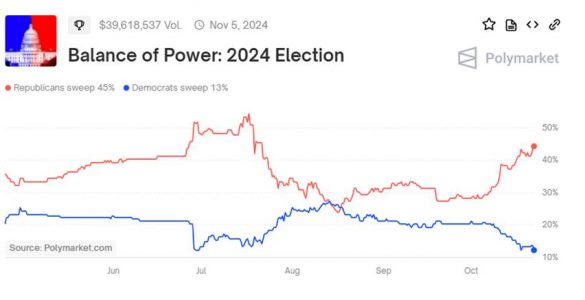

And the market has not stayed indifferent. As we noted last week, bets—whether naturally or strategically—show increasing positive inertia for the Republican candidate, impacting public debt investors’ confidence, who continue refining their expectations regarding rate cuts. As seen in the chart, the correlation between Trump’s winning odds and U.S. Treasury bond yields has risen significantly.

Kamala Harris leads by 1.8 points in the polls, while in 2020, Joe Biden held a ~7-point lead over Trump. Harris also trails Biden’s 2020 performance against Trump and Hillary Clinton’s (2016) performance in swing states (Michigan, Wisconsin, or Georgia).

Additionally, Trump clearly leads in voting intention among white, lower-education voters in these swing states, a relevant factor. Interestingly, despite declining unemployment, multiple surveys reveal that 60%-70% of respondents from different social groups (women, African Americans, independent voters, non-graduates…) believe the economy could be doing better, likely because real wage growth remains negative in many swing states.

To be fair, the macroeconomic outlook (with the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow forecast pointing to 3.4% growth this quarter and unusual September employment data) also plays a role. According to Polymarket, the probability of a “red wave” scenario consolidating Republican power in the White House and both houses of Congress is now at 45% and continues to rise. Realistically, Trump only needs to secure 12 of the 27 House seats in play for Republicans to take control.

The recent adjustments in stock, public debt, and gold prices, among other assets, mirror the patterns observed in 2016, indicating that investors are attempting to anticipate the November election outcome, already factoring in a potential Trump victory.

The fall in Treasury bond prices is logical. Under Harris’s plan, despite higher corporate tax rates, other initiatives—such as expanded social programs and tax credits—would significantly raise the deficit. Estimates suggest her policies could increase public debt by $3.5 trillion to $8.1 trillion by 2035, pushing the debt-to-GDP ratio from the current 102% to 133%.

Trump’s tax cuts, though unlikely to bring the rate down to 15%, would further widen the deficit, with estimates ranging from $1.5 trillion to over $15 trillion by 2035. His plan, especially with corporate tax reductions and potential tariff-based policies, would significantly cut federal revenue, making it harder to contain public debt growth. At best, tariffs could generate around $1 trillion in revenue, and efficient government administrative cost management another $2 trillion.

However, the most likely scenario remains a divided Congress, which would make it very challenging for either candidate to implement the more aggressive version of their fiscal agenda. While Trump could independently raise tariffs (60% for imports from China and 10% for others) without Congressional approval, this would effectively act as a tax increase, impacting household consumption and ultimately having a deflationary effect (similar to the Smoot-Hawley Act in 1930).

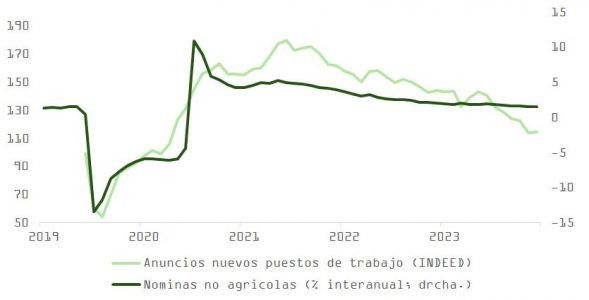

On the other hand, employment data continue to show a gradual decline in labor market activity. Caution is necessary, as too much emphasis should not be placed on September figures; a recent example of investor sentiment shifts occurred in early August. October data may be difficult to interpret due to hurricanes (Helena and Milton) and seasonal hiring for the holiday season. Seasonal adjustments may not suffice, and the data could undergo significant revisions. Additionally, real-time indicators show trends in job openings that don’t align with official figures.

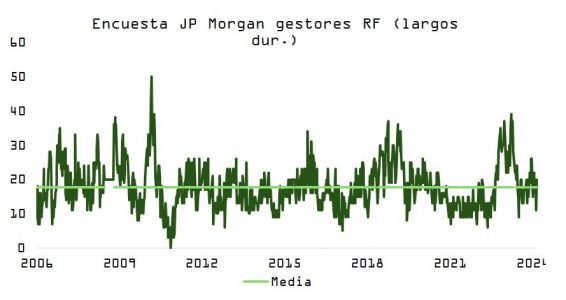

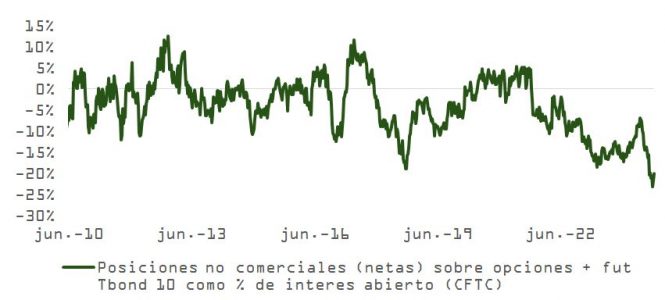

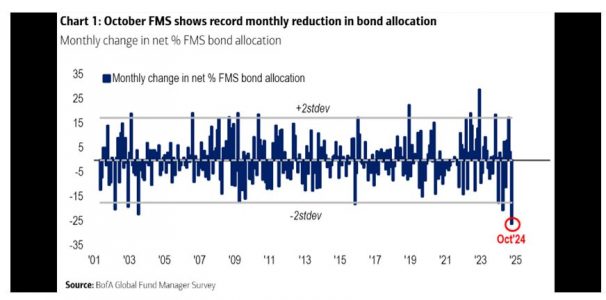

In contrast to the equities market, net speculative positions in U.S. 10-year bond derivatives have been aggressively reduced. This pessimistic sentiment is also evident in JP Morgan’s survey on duration positions and BofA Merrill Lynch’s survey among investment fund managers, who have rapidly scaled back their exposure to interest rate risk, as shown in the chart.

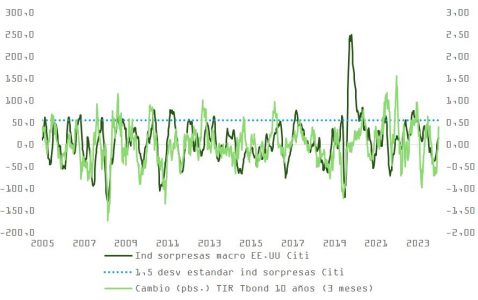

The T-Bond yield has over-discounted the macro surprise index’s upswing, which is nearing a turning point.

With official rates at 5%, and likely 4.75% in two weeks, the upward path for the T-Bond’s IRR should not exceed 4.8%. If a slowdown scenario—like in August—returns, we could quickly revisit the ≤3.5% zone. In a soft landing scenario, and if the terminal rate ends up above the dot plot estimate (~3.5%–3.75% vs. 2.875%), with a term premium of 0.2-0.4, yields would remain near current levels (~3.7%–4.2%), making the 12-month return distribution attractive, approaching 4.4%–4.5%.