Private credit has emerged as a popular asset class over the past decade, especially among sophisticated investors seeking diversification and attractive returns outside traditional public markets. In the following lines, we analyze this asset class from its inception, considering both the opportunities and the risks that must be carefully assessed.

Origins of Private Credit

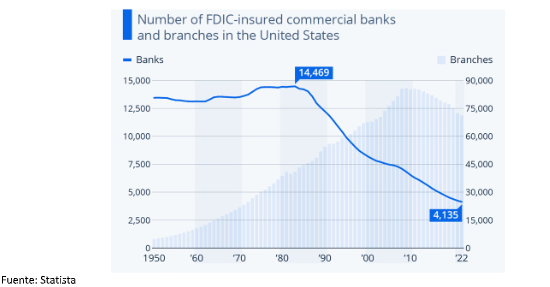

The birth of private credit is closely tied to the banking sector in the United States. As shown in the following chart, from the end of World War II until the 1980s, the number of banks in the United States ranged between 13,000 and 15,000. Following the financial crisis known as the Savings & Loans Crisis, the number of banks gradually decreased to 8,000. Later, due to the Great Financial Crisis, a second wave of consolidations reduced the number of banks to the current 4,000. Not only did the number of banks decrease, but the size of the surviving banks grew significantly, leaving a large gap in the segment of medium-sized banks that, in turn, served the middle market segment. This market went from having thousands of banks offering medium-sized loans to not having enough banks to request loans from, particularly during crisis periods.

This gap in the mid-small financial segment was filled by non-banking financial companies such as GE Capital or CIT and what is known as Business Development Companies (BDCs). BDCs can be public companies, listed on stock exchanges and registered with the SEC, through which investors, by purchasing their shares, provide the capital that is lent to medium and small companies. They can also be established as private companies or funds.

Classification of Private Credit

There are different ways to classify private credit into subcategories, each with its own characteristics and risk-return profiles. These categories include:

1. Direct Lending: Loans to medium-sized companies that do not have access to public capital markets. Direct loans are often collateralized and have strict covenants that provide additional protections for lenders.

2. Special Situations: Non-traditional lending scenarios where companies seek financing due to extraordinary circumstances or specific needs that are often complex and require customized solutions.

3. Mezzanine Debt: This type of debt is positioned between senior debt and equity in a company’s capital structure. It offers higher returns than senior debt but carries higher risk due to its subordination.

4. Distressed Debt: Investments in the debt of financially troubled companies. Distressed debt investors seek to benefit from the restructuring of these companies.

5. Asset-Based Financing: Includes loans secured by specific assets, such as real estate or inventory, providing an additional level of security for lenders.

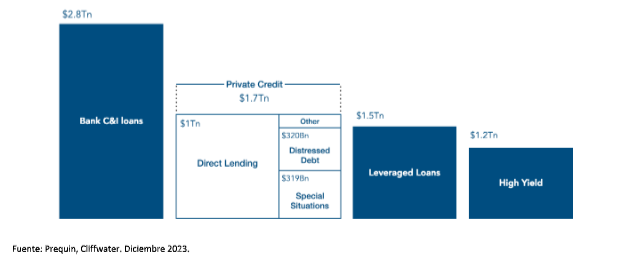

The following chart shows the main subcategories of private credit compared to traditional liquid fixed income and bank debt markets.

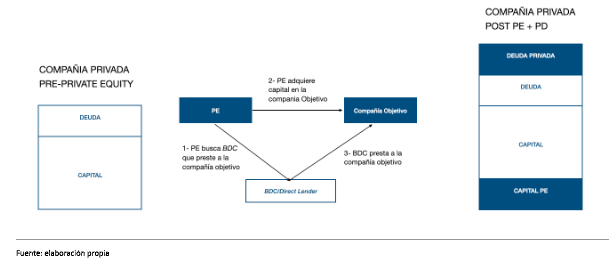

Relationship Between Private Equity and Private Credit – Sponsored Transactions

Often, transactions in the direct lending subcategory occur when a private equity (PE) fund wishes to acquire part or all of a company’s equity. The PE fund becomes the sponsor of the transaction and invites a BDC to participate by lending money to the target company, positioning itself in the senior part of the capital structure, protected by the sponsor’s equity injection. Due to these types of sponsored transactions, a significant percentage of private credit deal flow is closely linked to PE transactions.

Characteristics of Private Credit

Attractive Returns and Diversification

Private credit offers returns generally higher than those obtainable in public bond markets. These additional returns compensate for illiquidity and, in many cases, the greater complexity of these instruments. Some of the most notable characteristics of private credit are:

1. Inflation Protection: Since many private loans have variable interest rates, they can offer effective protection against inflation. This is especially relevant in economic environments where interest rates are rising.

2. Strong Financial Covenants: Private loans often include rigorous financial covenants that allow lenders to intervene early if the borrower’s financial situation deteriorates. This can include restrictions on the borrower’s ability to incur additional debt or make dividend distributions.

3. Flexibility and Customization: Private credit allows for greater customization in loan structuring compared to public bond markets. This flexibility can include payment terms tailored to the specific needs of the borrower and lender.

Risks of Investing in Private Credit

1. Credit Risk: The most obvious risk is that the borrower may not be able to meet its payment obligations. While financial covenants can mitigate some of this risk, it remains a crucial consideration. Private loans are often made to medium-sized companies that may be more vulnerable to economic cycles.

2. Lower Liquidity: Unlike public bonds, private credit instruments are not traded on liquid secondary markets. This means investors may have difficulty selling their investments before maturity without incurring significant discounts.

3. Complexity and Administrative Costs: Structuring, managing, and monitoring investments in private credit can be complex and costly. It requires a specialized and experienced team, which can increase operational costs compared to more traditional investments.

4. Interest Rate Risk: While variable-rate loans can offer protection against inflation, they can also expose borrowers to higher interest costs in a rising rate environment, potentially affecting their ability to pay and increasing credit risk.

Final Considerations

Given the above, does it make sense to include private credit funds in client portfolios at this time? It may not be prudent to give a generic “yes” without considering the characteristics and needs of investors, but an asset class with a 20-year history, nearly $2T in assets, and consistent results having weathered the Great Financial Crisis (2007-2008) and the 2020 pandemic deserves serious consideration. Let’s review some important details:

Firstly, the fact that institutional investors maintain positions in private credit provides great stability to the asset class. American pension funds, with a very long-term investment horizon, hold private credit investments ranging between 5%-10% of assets under management. Additionally, 38% of family offices (FOs) worldwide invest in private credit, increasing to 41% if the FO is located in the United States. On average, private credit investments make up 4% of total assets, although this varies depending on the volume under management.

Secondly, it is a strategy that produces and distributes cash flows, a highly valued characteristic during market panic or volatility. Additionally, as of the end of 2023, these cash flows are 30% higher than those provided by high yield bonds, and more than 100% over treasury bills.

Thirdly, the fact that it is a largely illiquid strategy reduces portfolio volatility and correlations with other asset classes, acting as a diversifier.

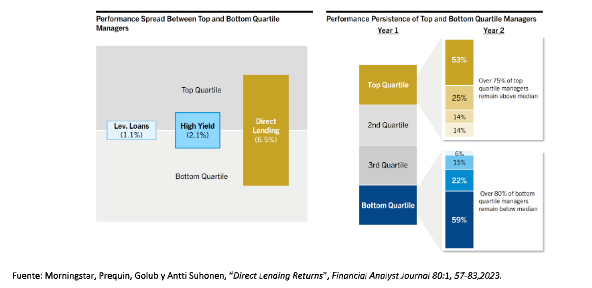

Finally, it is very important to highlight that the dispersion of returns among different private credit managers is substantially wider than among public credit managers, and the persistence in the different quartiles is very pronounced. This implies that the manager selection process is the determining factor, and it invalidates the use of averages as an indicator of the asset class’s performance.

Due to its private nature, access to information about different private credit managers is limited, making evaluation difficult. At Fund@mental, we have developed expertise in private funds and offer an analysis and due diligence service.

Analysis by Gustavo Cano, Founder and CEO of Fund@mental.