The inflation ambush of 2022 ended a decades-long downward trajectory for interest rates. While rates may fall a bit as the effects of tight financial conditions weigh on aggregate demand and economic growth, we don’t believe the cost of capital going forward will resemble anything like the levels of recent years when central banks artificially set market prices via quantitative easing. Just as water ultimately finds its own level, in my opinion, interest rates will find their own, higher level.

As a result of higher capital costs, companies will find it challenging to meet investor expectations. In past notes, we have argued this is part of a large paradigm shift from high and easy-to-earn returns on capital to something lower and harder. While higher borrowing costs are the most notable change, they are not the only factor driving the paradigm shift. This note focuses on one of the other factors: a secular increase in capital expenditures and what this may mean to profits.

Falling capital intensity was the past

Globalization, in particular China’s emergence on the global scene in the mid-1990s as the low-cost manufacturer, was game changing. While it catapulted China from economic dormancy to the world’s second largest economy, its impact reached far beyond China as it allowed developed market companies to become de facto asset-light businesses by outsourcing their manufacturing to lower-cost locales.

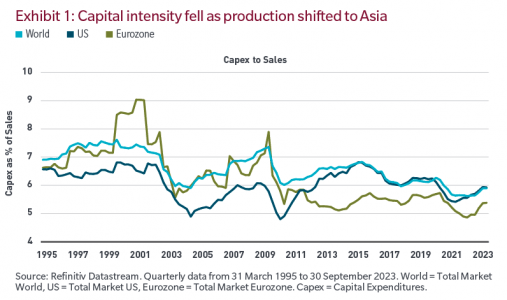

Companies no longer needed to rebuild tangible capital because China, and Asia more broadly, did it for them. As a result, capital intensity (capital assets compared with revenues) steadily declined, as depicted below.

This matters because there is a long-term and inverse relationship between capital spending and return on capital. When capital intensity falls, all else equal, returns rise because less capital was deployed. Tangentially, the outsourcing of production also pressured operating expenses due to reduced need for human capital.

The combination of financial leverage by way of artificially-suppressed rates and falling fixed investment drove historic returns for shareholders. But that came at the expense of savers and labor, and exacerbated income inequality. Both trends have ended.

Rising capital intensity is the future

The pandemic, followed by the Russia-Ukraine war, exposed the risk of not having goods available for sale when customers want them. To make a car requires thousands of parts, but it only takes one missing part to halt production. For companies, having a product available on the shelf at a lower margin has become more important than an empty shelf at peak margin. While the building of semiconductor and electric vehicle factories has captured the bulk of the media attention, reshoring and added capacity has extended across electrical goods, chemicals, medical equipment and more. Companies outside of technology and the automotive industry are spending money too.

A brewing cold war between the US and China, and more recently a war in the Middle East, have made this risk even more acute. While the magnitude is uncertain, we can expect deglobalization to divert capital — which in recent years was returned to shareholders via dividends, stock buybacks and acquisitions — to fixed investment. That will likely become a drag on future returns.

Why this matters

While in the short run, trading impulses, such as monthly labor or inflation data, drive asset prices, in the long term, it’s return on capital that matters. Looking ahead, the shift from supply chain efficiency to resiliency will mean that companies that are short of tangible capital will need to make capital investments that will negatively impact returns.

Much like investors, companies are capital allocators. Their stock and bond prices are scorecards, voted on by the market. We’re exiting an environment where the consequences for bad decision-making were blunted by the tailwinds of artificially suppressed rates and globalization. And we’re entering one with a reduced margin for error.

Returns may prove resilient for companies led by great decision makers who understood that COVID-era cheap capital and stretched supply chains were unsustainable. However, companies with high capital needs and elevated debt burdens may disappoint. Since returns drive financial asset prices, this should also bring a paradigm shift in the importance of security selection and active management.